Toddler's plea for life rests on an unrelated match

by Cindy A. AbolePublic Relations

Life is not supposed to happen this way.

Toddlers are supposed to be full of mischief, vibrancy and life.

Young

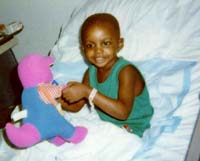

DeAndre' or “DJ” Simmons spends most of his

days confined to his hospital bed. At times, he seems to have just enough

energy to reach out for his mother's hand, reassuring himself of her nearby

presence. The gesture is nothing more than a small comfort between the

barrage of strange faces and poking needles which have invaded his life

in the past seven months.

Young

DeAndre' or “DJ” Simmons spends most of his

days confined to his hospital bed. At times, he seems to have just enough

energy to reach out for his mother's hand, reassuring himself of her nearby

presence. The gesture is nothing more than a small comfort between the

barrage of strange faces and poking needles which have invaded his life

in the past seven months.

His only hope lies in finding a successful bone marrow match—a gift that not even his mother and father can give.

“As a parent, it's easy to visualize your child growing up,” said Patricia Simmons, DJ's mother, who works in the hospital's radiology department. “You'd never think that your child would be anything but healthy.”

DJ joins the ranks of about 3,000 patients who are actively searching the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP) Registry in the hope of securing a match with an unrelated bone marrow donor. The program promotes bone marrow transplants for patients diagnosed with leukemia, sickle cell anemia and other life-threatening blood diseases. The organization recruits donors and maintains an international registry.

Of the 3.6 million Americans who are listed as potential donors with the NMDP, only about 281,000 donors or 7.9 percent are African Americans.

Today, African Americans are among a handful of minority groups that are underrepresented when it comes to bone marrow donations. Only Hispanic groups, Asians and American Indians fall further behind in the bone marrow donor pool.

“It's a worldwide problem,” said Debra Frei-Lahr, M.D., assistant professor of medicine, Division of Hematology and Oncology. “There are certain denominators within ethnic groups that are specific to their gene pools. These denominators help determine immune types within each individual.”

Genes come from within the family. Physical traits like hair texture and eye color are genetic characteristics. Genes also dictate an individual's immune response and its influence on marrow compatibility. This makes it difficult to match outside a person's own race and ethnic group. For minorities, matching patients to donors is less likely because of the limited donor pool.

According to the hospital's NMDP coordinator Paula Smith, pediatric patients undergo the most difficulty when it comes to bone marrow transplants. A child's condition is usually unstable and changing. “That's why timeliness is especially important,” she said. “It mostly depends upon the disease and at what stage the disease is in.” Marrow transplants are usually performed during the remission stage of a disease.

Not surprisingly, insurance plays a large role in a bone marrow patient's quality of care. Although a physician may approve a marrow transplant procedure, health organizations often dictate and approve coverage of certain types of antigen matches. Reflecting upon MUSC's research goals, the institution's transplant center performs both “five of six” and “six of six” transplants, the highest human leucocyte antigen (HLA) matched for donors.

So why aren't African Americans more active in donating their marrow, blood or whole organs?

Although religious beliefs might be one reason, the fear of doctors and a general mistrust in the nation's medical establishment might be another. At the heart of these suspicious attitudes is the horrible disclosure of a botched government experiment involving ailing black men who sought medical treatment for syphilis in rural Alabama. It is known as the Tuskegee experiment.

“People tend to remember bad experiences and stories,” said Jacquetta Jones, community educator and coordinator for the Program to Increase Donor Availability for African Americans. “In the south, there seems to be a culturally uninformed attitude exhibited by medical providers that promote a negative mistrust among blacks and the medical community.”

In 1998, bone marrow specialist Joseph H. Laver, M.D., professor of pediatrics, Division of Hematology and Oncology, proposed a program to help recruit and register African American donors statewide.

It is Jones' job to dispel these myths and turn attitudes around within African American and other minority populations. She also coordinates bone marrow drives and assists in educating communities about the values of marrow transplants as an efficient cure for many diseases. The project received funding and is listed among 28 Healthy South Carolina Initiatives which address health concerns throughout South Carolina.

For the past few years, Jones has organized 27 bone marrow drives only to register just 500 new donors to the registry.

“It's a tedious process,” said Jones, with the slightest bit of disappointment in her voice. “Usually, I'm always looking for new opportunities to talk with the public wherever I can find them.

Jones' most successful attempt was conducted last spring, when she coordinated a drive for Florence's African American community. The drive coincided with the devastating news that 19-year-old Keon Cooper, a hometown resident, was diagnosed with leukemia. His personal struggle helped inspire members of the community to respond. The Florence drive added 109 new members to the donor list.

Meanwhile, DJ is slowly dying as he awaits a lifesaving bone marrow transplant.

In a desperate effort, Jones is coordinating a bone marrow drive for DJ that will be held Aug. 9 at the MUSC campus. She hopes it will recruit many African Americans and anyone who wants to add their names to the registry. The need is so desperate that the American Red Cross waives the costs of a minority's lab fee ($75) which is usually required to process potential donors. Her efforts might give DJ and other patients from every ethnic background a better chance for finding matched donors.

“People seem to be aware that they must learn to respond to each others

needs,” said Jones. “For bone marrow transplant donors, there's no real

sacrifice to saving someone's life. What's important is they can live on

to see the results of their good acts.”

How do I become a marrow donor?

1. You learn about marrow donation and give a small blood sample.NMDP donor center representatives inform you about becoming a volunteer donor and the donation process. After you consent to being listed on the registry, you give a small amount of your blood.

2. Your marrow type is determined and entered onto the NMDP Registry.

Your blood is tested to determine its human leukocyte antigen (HLA)

type. The results are added to NMDP's main computer, which is searched

internationally on behalf of patients who need a marrow transplant.

3. You are contacted if a preliminary match is found.

If the computerized registry indicates that your marrow may match any

of the patients in need, your donor center coordinator informs you of your

status and arranges additional testing.

4. A compatible match is identified.

Further testing may indicate that your precise HLA-type is compatible

with the patient. Special counselors provide you with detailed information

about the marrow donation process and your options as a volunteer donor.

5. You decide whether to donate.

After being fully informed about the donor experience, you make the

decision to become a marrow donor.

6. A small amount of your marrow is collected.

In the hospital, marrow is extracted from the back of your pelvic bone

using a special needle and syringe. The donor is under anesthesia during

this simple surgical procedure.

7. You recover quickly from the procedure.

The marrow collection procedure typically involves one night in the

hospital. After being discharged, you can resume normal activity, although

you may experience some soreness for several days, a week or slightly longer.

Your marrow naturally replenishes itself within a few weeks.

Source: NMDP

Information on the Healthy South Carolina Initiative to Increase Donor Availability for African Americans is available by calling Jacquetta Jones, 792-8107.

For information about the National Marrow Donor Program, contact coordinator Paula Smith, MUSC Blood and Marrow Transplant Program, 792-9250.