Study: Brain stimulation helps depressed patients

The innovative treatment, called transcranial magnetic stimulation, or TMS, uses a magnet to stimulate a specific area of the brain.The therapy has been successful in helping people who are severely depressed, according to a study funded by the National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia and Depression (NARSAD).

Dr.

Ziad Nahas demonstrates the TMS technique on Dr. Ananda Shastri. Nahas

is holding the TMS coil which is connected to powerful batteries. A rapid

firing of electricity in the coil creates a brief powerful magnetic field

that passes unimpeded into Shastri’s brain, where it is then converted

into electrical impulses causing nerves to fire. It is safe and relatively

painless and is done while people are awake and alert.

Dr.

Ziad Nahas demonstrates the TMS technique on Dr. Ananda Shastri. Nahas

is holding the TMS coil which is connected to powerful batteries. A rapid

firing of electricity in the coil creates a brief powerful magnetic field

that passes unimpeded into Shastri’s brain, where it is then converted

into electrical impulses causing nerves to fire. It is safe and relatively

painless and is done while people are awake and alert.

The findings were published in a recent issue of the journal Biological Psychiatry by Mark George, M.D., and his colleagues at MUSC.

TMS entails the use of an external magnet to non-invasively stimulate the left prefrontal cortex, an area that previous brain imaging studies found to be functioning abnormally in people with depression. TMS treatment targets major depression—a life-shattering illness that can rob people of the will to live.

“This new tool allows us for the first time in the history of mankind to non-invasively stimulate the brain while the person is awake and alert,” said George, a professor of psychiatry, radiology and neurology, and director of the Brain Stimulation Laboratory at MUSC. “We know that depression and other diseases we struggle with involve the brain and circuits in the brain.”

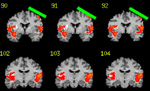

These

are coronal MRI slices through the brain, oriented as if the person is

shaking your hand. The TMS coil location is in green. The areas in color

are brain regions that have increased activity when the TMS coil is on

compared to when it is off. It is likely through changes in these brain

regions that TMS exerts its antidepressant effects. MUSC is the first in

the world to be able to perform TMS within an MRI scanner.

These

are coronal MRI slices through the brain, oriented as if the person is

shaking your hand. The TMS coil location is in green. The areas in color

are brain regions that have increased activity when the TMS coil is on

compared to when it is off. It is likely through changes in these brain

regions that TMS exerts its antidepressant effects. MUSC is the first in

the world to be able to perform TMS within an MRI scanner.

For his study, George enrolled 30 severely depressed patients who had not been helped by medication or could not tolerate the side effects. Most of the participants struggled with thoughts of suicide every day. Twenty patients received 20 minutes of TMS each weekday morning over a two-week period. A control group of 10 patients had the magnet placed on their scalp, but did not receive the treatment. Participants did not know who was receiving the actual treatment.

Researchers placed a small coil of wire on the patient’s scalp and passed a powerful but painless current through it, producing a magnetic field that passed unimpeded through the skull. The magnetic field, in turn, produced a much weaker electrical current in the brain. Patients felt no pain from the current, but may have experienced some discomfort during a muscle contraction. One person dropped out of the study due to the discomfort.

Participants receiving TMS showed significant improvement in their depression, according to the study. Using depression rating scales, nine out of 20 patients receiving TMS reported a 50 percent reduction in their symptoms, while no patient in the control group improved. The treatment had no side effects except for a mild headache reported by one-third of the participants, which was relieved by over-the-counter pain medication. TMS did not affect memory.

One 23-year-old patient said TMS lifted the dark depression that had hung over her life for nearly 10 years. She had tried close to 10 different medications, with no relief. Unable to function, she was forced to drop out of college. “The depression was overwhelming. I was so tired all the time, I couldn’t get out of bed,” she recalls.

After TMS therapy, she experienced happiness for the first time in years. “From the beginning, I started feeling better. It was like it opened a door for me.” She has been able to resume her studies. The young woman continues to receive TMS as a “maintenance” treatment one day a week in another study being conducted by George.

Although researchers do not completely understand what causes depression, they theorize that it is due, in part, to a kind of short circuit in the brain. Several years ago, emerging knowledge of mood-regulating circuits prompted researchers to start looking at TMS as a possible treatment. The next question was which area to target. Because MRI studies of the brain had shown the prefrontal cortex to undergo changes in depressed patients, researchers targeted that area. “Neurobiologic mechanisms are not well understood,” George acknowledges. “Much of our work was based on good guesses and hunches.”

Depression affects 19 million people in the United States alone and is one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. Help has traditionally come in the form of antidepressant medication, psychotherapy or a combination of both. For those whose depression does not respond to conventional treatment, TMS may offer a viable alternative, according to George. “We are hopeful this therapy will not only lead to better treatments, but will give us more clues to help solve the riddle of depression.”

Further TMS studies of longer duration with greater numbers of participants are needed, according to George, who notes that researchers are conducting TMS trials at about 20 major medical centers worldwide. George is currently involved in another NARSAD-funded study in which patients receive treatment inside a functional MRI scanner. The scanner takes pictures inside the brain to show what happens during the treatment and can help researchers determine the most effective way to administer TMS therapy.

“The fundamental question remains,” said George, “if TMS works, how

does it work? The brain imaging should help us to figure that out.”