Study shows limitations of virtual colonoscopy

A multicenter study led by MUSC showed computed tomographic colonography, also known as virtual colonoscopy, to be much less effective in detecting lesions in the colon than the standard colonoscopy.The results of the study was published in the April 14 issue of the Journal of American Medical Association (JAMA).

Six hundred subjects from nine medical centers across the United States and England underwent both the virtual and standard colonoscopy procedures. The researchers found that the virtual colonoscopy detected only 39 percent of subjects with at least one lesion greater than or equal to 6 mm and only 55 percent of subjects with at least one lesion greater than or equal to 10 mm. Conventional colonoscopy detected 99 percent and 100 percent, respectively, for the two sizes.

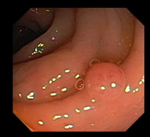

During

a standard colonoscopy, a polyp (left photo) is snared (right photo) by

a loop of sharp wire extending from a long, flexible lighted tube (a colonoscope)

that has been inserted into the rectum and guided slowly into the colon.

The wire snips the polyp, which is retrieved in the tube and moved out

of the colon for biopsy. Anything abnormal, such as a polyp or inflammation,

can be removed in whole or part by tiny instruments passed through the

colonoscope.

During

a standard colonoscopy, a polyp (left photo) is snared (right photo) by

a loop of sharp wire extending from a long, flexible lighted tube (a colonoscope)

that has been inserted into the rectum and guided slowly into the colon.

The wire snips the polyp, which is retrieved in the tube and moved out

of the colon for biopsy. Anything abnormal, such as a polyp or inflammation,

can be removed in whole or part by tiny instruments passed through the

colonoscope.

The study was initiated and planned by MUSC’s Digestive Disease Center and the Clinical Innovation Group, who collected and housed the data from all nine centers and provided the statistical support to analyze the data. The participating clinical centers were MUSC’s Digestive Disease Center, Wake Forest University School of Medicine, Emory University Hospital, Indiana University Hospital, the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, the Medical College of Virginia, St. Mary’s Hospital (London), M.D. Anderson Cancer Center and University Hospital of Cleveland. The Office of Naval Research of the U.S. Department of Defense supported the study.

Peter Cotton, M.D., director of MUSC’s Digestive Disease Center, was principal investigator of the multicenter study and Brenda Hoffman, M.D., was principal investigator for the MUSC site. Valerie Durkalski, Ph.D., and Yuko Palesch, Ph.D., of MUSC’s Clinical Innovation Group were study statisticians. Patrick Mauldin, Ph.D., associate professor in MUSC’s College of Pharmacy, served as co-investigator with the Clinical Innovation Group.

Conventional colonoscopy was developed in the early 1970s and has been a routine tool for examining the colon. It was initially used to diagnose individuals who had symptoms such as bleeding. Screening for asymptomatic patients became popular in the last five to 10 years, as data has grown showing that detecting and removing pre-cancerous lesions in the colon prevents them from growing into cancer. Colonoscopy as a screening tool for individuals over the age of 50 has been recognized by the major cancer organizations, and costs for the procedure are reimbursed by insurance companies. Most lesions discovered during colonoscopy can be removed during the same procedure. But because the test is invasive and perceived as an unpleasant experience, many people who could potentially benefit have resisted the screening.

Also, during the past 10 years researchers began investigating virtual colonoscopy, a technique that uses a CT scanner and computer virtual reality software, enabling a radiologist to “see” the inside of the colon through the examination of computer-generated images of the colon constructed from data obtained from an abdominal CT examination.

If a lesion was detected through virtual colonoscopy, the patient would have a conventional colonoscopy performed to remove any lesions.

A number of recent clinical studies reported detection rates from virtual colonoscopy to range from 84 to 94 percent. Most of these studies were initiated by committed radiologists, many of them pioneers in the technique, and were restricted to a single center. But to be valuable as a screening tool, virtual colonoscopy must perform well in routine practice. The MUSC researchers’ objective was to assess the accuracy of virtual colonoscopy in a large number of subjects across multiple centers.

An interesting outcome of the study was that only one of the centers had a relatively high detection rate with virtual colonoscopy, and this was the center that had prior substantial involvement with the virtual techniques. That center had the largest number of participants—184—and had an 83 percent detection rate. The detection rate for all the other centers combined was 26 percent. The high-detection rate center’s results were consistent with that center’s already published results and those of several other single-center, small-scale studies.

The MUSC researchers noted the poor results from their study, with the exception of the one highly experienced center, compared to the good results of earlier published studies coming from centers with radiologists who were pioneers in the technique. This led them to conclude that though previous studies have shown virtual colonoscopy to be successful in the hands of experts, the technique is not ready for routine use.

“I hope our study will stimulate more studies on improving both technique, software, scanners and training, so that virtual colonoscopy will eventually provide an accurate, non-invasive screening tool,” said Cotton. “If virtual colonoscopies are improved so they are as effective as the conventional colonosocopy, many more people would get screened, and more precancerous lesions would be detected. These lesions would be removed by the conventional colonoscopy and cancer would be prevented.”

From the patient’s perspective, the worst part of the procedure is the bowel prep. It is necessary to take medication to clear out the bowels prior to either procedure. “If the computer techniques can be improved to eliminate the bowel prep, this would revolutionize the whole thing,” Cotton said. He said there are ongoing studies exploring the “virtual bowel prep.” This entails giving patients something to drink that mixes with residue in the colon until the material reaches a certain density. Then a button can be pressed on the CT machine to ignore anything of that density.

Another future issue that would make a big difference in the success

of virtual colonoscopy is the development of software to recognize lesions.

For each study, the radiologist must look at more than a thousand pictures,

and in a screening situation you find something in only one in five patients.

“You sit there all day, looking at thousands of images, most of which are

normal, so it’s difficult to pick the ones that stand out,” Cotton said.

“I’m not suggesting that computers would take over, but they can flag things

and potentially make the process more effective.”

MUSC physician weighs merits of both procedures

by Michael BakerPublic Relations

Colonoscopy. Say the word, watch people cringe.

Seeing the instrument doesn’t alleviate the fear, either. The business end of the scope stretches nearly four feet. Of course, that’s four feet more than most people are willing to accept.

But

Jay Robison, M.D., professor of vascular surgery, had both a virtual and

conventional colonoscopy as a participant in MUSC’s multicenter clinical

trial comparing the two procedures.

But

Jay Robison, M.D., professor of vascular surgery, had both a virtual and

conventional colonoscopy as a participant in MUSC’s multicenter clinical

trial comparing the two procedures.

“The worst part about a colonoscopy, virtual or real, is the anticipation,” he said. Robison sees the positive and negative aspects of both procedures.

“With the virtual colonoscopy, you’re not sedated. You could probably drive yourself home afterwards,” he said. “Granted, with the virtual colonoscopy, as well as the conventional colonoscopy, there’s some discomfort due to the preparation process—the bowel cleansing. But even this procedure produces minimal discomfort, especially when you compare today’s methods with those in the past.

“During a traditional colonoscopy, the doctors run an IV so you’re sedated. There’s less discomfort in that sense,” he said. However, he added that sedation posed an obvious problem with functioning for a brief time following the procedure.

After having both procedures (and knowing that if a lesion were found during a virtual colonoscopy, a conventional version would follow), Robison came to a conclusion.

“If I had to choose, the traditional colonoscopy is probably the most efficient use of your time and provides the least discomfort,” he said. The results of the clinical trial reinforced his decision.

According to both Robison and Peter Cotton, M.D., director of the Digestive Disease Center and principal investigator in the clinical trial, colon cancer is the second most prominent cancer among men and women. It trails only lung cancer.

“Most people have some connection to colon cancer,” Robison said, “whether they’ve had it or know someone who has. Colonoscopies are so important because if you detect colon cancer in its early stages, it’s largely curable.”

Robison’s experiences as a colonoscopy patient allowed him to see things from a perspective other than that of a physician. “I try to suspend my persona as a physician when I’m on the other side of things,” he explained. “It’s interesting to be on the receiving end of health care. I noticed the little things—the amount of time spent in the waiting room, the dynamic between the patients and health care professionals. My experience reiterated the importance of the little things in health care.”

Similarly, colonoscopies reiterate the importance of details. The procedure

carries an undeservedly unpleasant reputation, but it’s a little thing

that can make a big difference.

Friday, April 16, 2004

Catalyst Online is published weekly, updated

as needed and improved from time to time by the MUSC Office of Public Relations

for the faculty, employees and students of the Medical University of South

Carolina. Catalyst Online editor, Kim Draughn, can be reached at 792-4107

or by email, catalyst@musc.edu. Editorial copy can be submitted to Catalyst

Online and to The Catalyst in print by fax, 792-6723, or by email to petersnd@musc.edu

or catalyst@musc.edu. To place an ad in The Catalyst hardcopy, call Community

Press at 849-1778.