|

|

|

|

Harveting youth: Aging Center's goal

|

by Dawn Brazell

Public Relations

Lotta Granholm, Ph.D., DDS, leans down and picks plump blueberries off

the bushes in her yard. She offers up a handful, practicing what she

preaches as director of MUSC’s Center on Aging.

Dr. Lotta

Granholm picks blueberries from a bush in her yard. The director

of MUSC’s Center on Aging encourages healthy lifestyle habits to

promote brain health. Dr. Lotta

Granholm picks blueberries from a bush in her yard. The director

of MUSC’s Center on Aging encourages healthy lifestyle habits to

promote brain health.

The neurosciences professor knows from her research at MUSC what a

potent protector this fruit can be in keeping brains healthier and

dementia-free. It’s convincing enough that she has the bushes growing

in her yard, and she’s out beating the bushes hoping more people will

hear about the advances in aging research and use the Center on Aging’s

growing resources.

The center has ambitious plans, but it needs to, said Granholm.

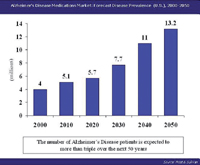

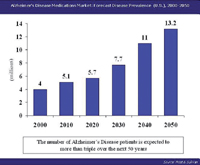

The

center supports aging research, such as studying neurofibrillary

tangles, pictured to the left, that form in the brain of people with

Alzheimer’s disease. The

center supports aging research, such as studying neurofibrillary

tangles, pictured to the left, that form in the brain of people with

Alzheimer’s disease.

“The loftiest goal we have is to actually improve longevity in South

Carolina. The average lifespan here is lower than most other states,

and about five years lower than the national average.”

The nation’s aging demographics prove the need for action. The baby

boomers are hitting their 60s, and it has been calculated that 10,000

people will turn 60 every day for the next 20 years. Because of an

increased lifespan, the population of those more than 85 years will

increase fivefold in that same period, she said.

Compounding the problem is that fewer than .5 percent of health

professionals are trained in geriatrics, despite that 40 percent of

doctor’s visits are for elderly people.

The center, which is the oldest research organization at the

university, hopes to change that and position the university and state

to better handle an aging population. One method is to increase the

volume and quality of research concerning aging with the center serving

as a clearinghouse for the scientists, health professionals,

private-sector partners and the public who want easy access to the

latest resources on aging, she said.

Another method is to promote the close interaction within MUSC of the

various specialty areas involved with aging from MUSC’s Movement

Disorders Program and its Alzheimer’s Research and Clinical Programs to

the newly-funded Aging Q3 in the Department of Medicine, a residency

training program aimed at improving physicians’ care of the elderly.

The center truly spans across all colleges, focusing on service,

education and research, she said. “We feel a big mission in terms of

connecting different researchers across campus. So if anyone is

interested in finding research about stroke or macular degeneration or

anything related to aging, they can come to us.”

The center also can assist with research funding. For example, it

recently helped secure a pilot grant for a Parkinson’s disease study.

“With just one year of funding from the Center on Aging, researchers

were able to find six drugs that have potential that we will now

pursue. With a small template of money, we are able sometimes to make a

big difference.”

Community

outreach

To address the complex and seemingly overwhelming health needs of the

elderly, the center is collaborating with other agencies, including the

state’s Office on Aging, S.C. Aging in Place Coalition, the South

Carolina Aging Research Network (SCARN) and the University of South

Carolina’s SeniorSMART program that promotes research and technology to

help the elderly maintain their independence and cognitive skills.

Granholm said MUSC is a partner in the SeniorSMART program with its

SeniorHOME and SeniorBRAIN divisions representing an exciting area of

growth.

“It will get devices out to people, and maybe the state will be able to

provide funding for those who can’t afford it,” she said, explaining a

movement sensor device being developed that can detect when an elderly

person has fallen at home. “Falls are a huge factor as far as quality

of life. Just being able to have that device in their house allows

seniors the ability to live independently and gives loved ones peace of

mind.”

Another important goal is to educate medical students about the

differing needs of elderly patients. The center brought the Senior

Mentor Program to MUSC in 2005 to better prepare MUSC medical students

to meet the needs of an aging population. The program pairs two medical

students to a senior mentor volunteer in the community aged 65 or

older, with the students working with their mentor the entire four

years of their medical school training.

Rebekah Hardin, education coordinator, said that the program is one way

to better educate medical students to be more sensitive to the needs of

elderly people. It allows students to understand on a personal level

how it’s not easy for everyone to pay for aging, Hardin said.

“You can see such a bond created through the four years. We’ve gotten a

great response from students about how it’s helped them see the

stereotypes they have about seniors.”

Not only does the program improve the quality of elderly care the

students will be able to offer, it also sparks an interest in

geriatrics as a specialty for some of them, said Hardin. The

program is being expanded across other colleges, with pharmacy being

added this fall, an exciting addition given the problems of

polypharmacy or the use of multiple medicines in the elderly, she said.

Granholm said the mentor program is the perfect platform for her to

raise awareness among students of the latest research they should be

passing along to their patients. As part of the program, she teaches

the students the importance of the simple things they can teach their

patients to improve quality of life. “I tell them, ‘You are the next

generation. You need to teach every patient—every age that comes in

here—you need to prescribe exercise and the low-fat diets.”

Fountain of youth

Though her community talks focus on aging, it’s not unusual to find

Granholm delivering her message to a young audience of school children.

She knows that’s when lifestyle habits start.

The life expectancy for women in the state is decreasing every year,

she said. “It’s primarily eating habits and lack of exercise. It’s

amazing that the life expectancy for women in South Carolina is

decreasing every year, contrary to the developing countries where it is

increasing. That’s shocking to me and disturbing.”

She attributes this to poverty, lower educational levels and unhealthy

eating habits. Studies have shown that early obesity leads to less

healthy aging. Obesity is a risk factor for many conditions, including

Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases as well as diabetes, stroke,

cancer and cardiovascular disease. Granholm wants people to get the

connection between unhealthy eating and how that can affect their

brains and accelerate aging.

In South Carolina, the average life expectancy is 75.8 compared with

the national average of 78, and South Carolina is ranked 40th in

longevity according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Claudia Umphlet, a

research specialist, assists Dr. Granholm with her research on aging as

she slices brain tissue that will be stained in order to view specific

cellular components. For information on the Center on Aging, visit Claudia Umphlet, a

research specialist, assists Dr. Granholm with her research on aging as

she slices brain tissue that will be stained in order to view specific

cellular components. For information on the Center on Aging, visit

http://www.musc.edu/aging or SeniorSMART at

http://www.sc.edu/coee/seniorsmart/smarthomeendowedchair.html.

One of the focal areas of her research is to study the diets of people

and to relate it to research being done on the brain, particularly now

that MUSC has its own brain bank, the Carroll A. Campbell Jr.

Neuropathology Laboratory.

“Once we can connect and show people ‘here is what happens to your

brain if you eat this diet,’ it’s a powerful message we can go out

with.”

Granholm said

she’s had threats from fast-food companies and some parents who have

complained that their children refuse to eat fast-food fare after one

of her talks. It’s a complaint she likes, though, because it means the

students have made the connection between bad lifestyle habits and the

diseases of the brain that they can impact. Granholm said

she’s had threats from fast-food companies and some parents who have

complained that their children refuse to eat fast-food fare after one

of her talks. It’s a complaint she likes, though, because it means the

students have made the connection between bad lifestyle habits and the

diseases of the brain that they can impact.

“If you eat more than a few percent of transfats in your diet

regularly, you will double your risk for Alzheimer’s. In contrast, if

you just walk your dog for half an hour three days a week, you will cut

your risk for Alzheimer’s disease in half. This is what I constantly

talk to people about—moderate exercise. It doesn’t have to be a lot.”

Brain

bank

expands

aging

research

Nicholas Gregory is used to getting funny looks when he tells people

his job title.

Explaining that he’s the brain donation coordinator of MUSC’s brain

bank can be a conversation stopper. But not for long.

Gregory is quick to tell them about the Carroll A. Campbell Jr.

Neuropathology Laboratory that just opened December 2009 and to

highlight the important brain tissue research being done—research

that’s a critical component in finding cures for such devastating

conditions as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and stroke.

Lotta Granholm, Ph.D., DDS, director of MUSC’s Center on Aging and

co-director of the Carroll A. Campbell Jr. Neuropathology Laboratory,

said the brain bank represents a big step forward in establishing a

neuropathology core at the university and in advancing research on

aging.

“The research we’ll be able to do with the brain bank—with the human

brains—is really exciting. We now have 13 brains, and we’re partnering

with other departments to get researchers interested in the human

tissue. The more interest that is raised creates more awareness and

leads to more brains donated.”

Nicholas Gregory

holds a brain used

for resarch at the MUSC’s brain bank, which opened December 2009. The

bank now has 13 brains being used for research. Nicholas Gregory

holds a brain used

for resarch at the MUSC’s brain bank, which opened December 2009. The

bank now has 13 brains being used for research.

Gregory said the brain bank will make it easier for local researchers

to procure tissue without having to navigate the logistics of getting

it from other states. “We can look at the South Carolina population,

which in turn is the same people our doctors and clinicians are dealing

with, which is comparing apples to apples. We can lead research trials

here and come up with novel ideas and solutions for these problems.”

The laboratory does a postmortem diagnoses on the donated brains in

order to give closure to families, but also so the tissue can be

characterized and researchers can get the types of brain tissue they

need.

“The only way to accurately diagnose Alzheimer’s disease as well as

other neurological disorders is through a postmortem diagnosis,” he

said. “Also, the best way to study these diseases is to look at human

tissue, as mouse and rodent models do not accurately mimic the diseases

we see in humans.”

The state having its own brain bank will also help to solve the health

disparity problems that are unique to this state, which has a higher

incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, diabetes and stroke.

“We want to find out why this is. What is unique about our state that

is causing us to have these high rates of these diseases? The state has

a higher African-American population compared to the rest of the

country and this population is known to have a much higher risk of

developing Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes and is at greater risk for

stroke.”

According to the American Heart Association, South Carolina is sixth

highest in stroke related-deaths. In a recent report from the 2010

Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures from the S.C. Alzheimer’s

Association, the state has the fourth highest incidence of deaths due

to Alzheimer’s disease.

Gregory said the brain bank offers an exciting resource to discover

more about the disparities between racial and ethnic groups. It also

allows research to move faster in discovering causes and treatments for

many different kinds of neurological diseases. The bank currently has

brains from people who have had Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases,

brain tumors and progressive supranuclear palsy.

“People are excited about this and see that it’s a great opportunity

for the state and for MUSC. It truly can do a lot of good here. We

already have a lot of clinical programs set up that we can collaborate

with. I think we can really make some progress.”

Gregory said the organ donation that people designate on their driver’s

license does not cover the brain. Brain donation requires a donor

registration form and also notification of the next-of-kin, who will be

required to sign a postmortem consent form after death. Anyone can

donate, except for people with certain infectious diseases such as AIDS

or Hepatitis.

Because people suffering from neurological disorders often understand

the need for research, the bank receives many of those types of

donations. It also needs “normal” or non-diseased brains, though, that

can be used as controls in studies, he said. The bank has 13 brains,

with it receiving one every other week. The goal is to increase it to

one a week.

Gregory said neuroscience is an exciting field, with the past decade

seeing an exponential growth in research. “As much as we’ve studied,

there’s still a long way to go.”

Having a local brain bank encourages more local people to make

donations, since research shows people are more likely to donate to a

state-supported program, he said.

“It’s a gift of hope and a way people can give back to their community.

Most people have the heart on their driver’s license. They are willing

to donate their organs to potentially save someone’s life. We believe

this is just as important.”

For more information or to print out a donor form, visit

http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/aging/research/Brain%20Bank/Homepage.htm.

Friday, Aug. 13,

2010

|

|

|

Granholm said

she’s had threats from fast-food companies and some parents who have

complained that their children refuse to eat fast-food fare after one

of her talks. It’s a complaint she likes, though, because it means the

students have made the connection between bad lifestyle habits and the

diseases of the brain that they can impact.

Granholm said

she’s had threats from fast-food companies and some parents who have

complained that their children refuse to eat fast-food fare after one

of her talks. It’s a complaint she likes, though, because it means the

students have made the connection between bad lifestyle habits and the

diseases of the brain that they can impact.