|

In what could be a

science fiction scenario, Dvora Beeri became MUSC's first patient to

undergo brain surgery March 29 as part of a clinical trial to see the

effectiveness of CERE-110, a new type of gene therapy treatment for

patients with Alzheimer's disease.

By Dawn Brazell

Public Relatins

Jacobo E. Mintzer M.D.,

co-principal investigator with neurosurgeon Istvan Takacs, M.D., said

Beeri is the first in the state and the 19th in the world to have the

procedure done as part of a Phase 2, double-blind study involving

patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease.

"We're skeptically

optimistic. We're opening a new door that we don't know where it's

going to lead us, but we're opening it locally in a way that puts us on

par with the top centers in the world," Mintzer said.

Dr. Jacobo

Mintzer Dr. Jacobo

Mintzer

MUSC is one of 10 leading

centers across the U.S. that has been selected to be a part of the

study, which is being conducted in collaboration with the Alzheimer's

Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS). Mintzer, who is director of the

Department of Neurosciences a Division of Translational Research, said

the trial is a sign of the success of ADCS, a national research

consortium funded by the National Institute on Aging that conducts

multi-center clinical trials.

Given the prevalence and

devastation of Alzheimer's disease, this work required a network of

sites with state-of-the-art capabilities where any new treatment or

approach could quickly and effectively be put in the pipeline and

tested, Mintzer said. It was noticed that true innovation wasn't

necessarily coming from pharmaceutical companies but from small biotech

companies who oftentimes did not have the resources to move the science

forward.

The ADCS selected the 30

top centers in the country to form a network to aid these small

companies and implement clinical trials on a national level to move

this science forward faster through its grant system. Of those centers,

10 were selected for this study.

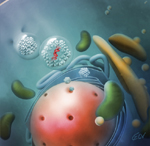

Gene therapy involves nerve growth

factor being injected into a critical area of the brain called the

Nucleus Basalis of Meynert. Medical

illustration by Emma Vought Gene therapy involves nerve growth

factor being injected into a critical area of the brain called the

Nucleus Basalis of Meynert. Medical

illustration by Emma Vought

The science being promoted

in this case studies how best to get NGF or nerve growth factor to a

critical area of the brain called the Nucleus Basalis of Meynert (NBM),

a brain region where cell degeneration occurs in Alzheimer's disease.

CERE-110 is composed of an adeno-associated viral vector carrying the

gene for NGF, a naturally occurring protein that maintains the survival

of nerve cells in the brain.

CERE-110 is surgically

injected into the NBM, where it is hoped the delivery of NGF gene using

a "virus" will allow NGF to replicate itself through the patient's own

cell machinery and stop the progression of the disease or even

potentially cause improvements.

"We have to get it in the

right place in a way the cell can incorporate it," said Mintzer. "We

need to get the cell to generate it by itself on an ongoing process.

The only way you can do that is by injecting new DNA into a cell."

Beth Safrit, left, and Dvora Beeri Beth Safrit, left, and Dvora Beeri

Beth Safrit, nurse

practitioner III and clinical director of the Department of

Neurosciences Alzheimer's Research and Clinical Programs, will oversee

the monitoring of the five to 10 patients who will be participating in

the trial. The patients are followed for 24 months.

"It's the only thing out

there that can offer any true hope of improving," she said of the

study, which accepts patients who have only a mild level of

Alzheimer's. "If these patients can stabilize themselves or maybe even

get a little bit better with this one-time treatment, because that

little virus is producing for the rest of their lives, it's an amazing

thing. If it proves to be effective, it's going to change their lives

forever."

Mintzer said one of the

main challenges is pushing the science forward, while managing people's

expectations. It will be years before a therapy can be developed should

the therapy prove effective. Having begun his research into Alzheimer's

disease in 1981, Mintzer said he's seen impressive changes from when it

was difficult just trying to convince people that such a disease

existed.

"Now we have come to a

moment where we are inserting new genetic material into cells."

It's been a complex

process to bring the study to MUSC, with more than 400 people having to

be trained in the MUSC family, from the pharmacists and doctors

involved to the person cleaning the OR. Safrit holds up a thick file

folder of all the employees who had to be checked off. Though they

received no extra pay, they were willing to do the training.

"They were enthralled with

what we were accomplishing here," she said. "They were happy to be a

part of it."

The other critical part

that enables the study to proceed are the patients who are willing to

take the risk of a double-blind study, which means they will have their

head shaved and may go through a "sham" surgery where they don't

receive the gene therapy. The patients and researchers won't know until

the end of the two-year study who received the real treatment, although

eligible patients who received the sham surgery will be offered the

therapy at the end if they want it.

Mintzer said it takes a

very strong commitment from the person. It takes a commitment from MUSC

as well.

"A few years ago, this

appeared to be science fiction. I'm excited not only about this

particular study but about the possibilities it opens for us

scientifically. It lays the groundwork for gene therapy for other

organs. There is a path that has been laid out, and that puts MUSC

clearly on the forefront for this type of research and eventually, this

type of therapy."

MUSC has one of the few

neuroscience programs in the country to have neurosurgery working with

neurology and Alzheimer's specialists, which is not a common event, he

said.

"This project requires a

very close collaboration between neurosurgery and the dementia

specialists. We have both together at MUSC. The core of our MUSC

mission is to bring to South Carolina what would not be available if

the resources of a university of this caliber were not here."

For more information about

the clinical trial, call 740-1592, ext. 14 or visit http://academicdepartments.musc.edu/arcp/.

Alzheimer's patients

hope gene therapy study works

Avri Beeri knows his

research.

He can tell you everything

there is to know about Alzheimer's disease—about the myriad of clinical

trials, the vitamins and supplements thought to slow the process, and

how he helped his wife to be part of an elite group of only 50 people

who will be in Phase 2 of the CERE-110 clinical trial. He can tell you

what it's like to live with a spouse who suffers from a disease that

requires him to be watching with "10 eyes all the time what is going

on."

He smiles lovingly at

Dvora, his wife of 44 years, who has returned to MUSC for a check up

following her brain surgery March 29, where she may have received gene

therapy as MUSC's first patient to enroll in the trial. Their hope is

that this therapy will stop and possibly even improve her condition.

Avri

and Dvora Beeri Avri

and Dvora Beeri

Sporting a new cap to

cover her closely-cropped hair, Dvora smiles at her husband. "I just

need to remember," she said of her decision to enter in a double-blind

clinical study that required her to have a portion of her head shaved

for a treatment she may or may not have received when she underwent

surgery.

Beeri nods at his wife's

response. He needs to know he did everything he could to help her do

just that.

He's the memory keeper for

both of them now. Beeri met his wife when he went to take music lessons

from her brother. "He invited me to come home with him, saying 'I will

teach you some lessons.' I never learned how to play the guitar,

but I learned her," he said, smiling.

Beeri found out his wife

had Alzheimer's disease four years ago, when his life researching the

disease began. He reads everything he can trying to find out what can

break the cycle and stop the disease. "I'm constantly Googling all over

the world to find out what study she could go on."

When he ran across the

nerve growth factor research, he knew he wanted to get her into a

study. On a wait list at Duke University, the couple decided to move

forward with doing the clinical trial at MUSC, where they had

participated in a previous study.

"I was following it very

closely to see where it was going to be, and when I found out it was

going to be here, I thought, 'Good, I know these people.'"

Beeri said they've been to

MUSC so much, his car comes on auto-pilot now. The decision to

participate in the trial was simple for him, but not as much for Dvora.

"She was the one who had to be drilled," he said of the holes that

surgeons have to make for the patient to receive the gene therapy. "I

told her, 'If I were the one who had it, I would do it.' If anything

could stop it, it's worth trying it even with all the pain."

Consulting with their

internist in Charlotte, Beeri said he was relieved it took the doctor

10 seconds to advise to do it. "We talked to him together. He said he

would do it for himself."

Dealing with the disease

takes patience. He advises other caregivers to know how fast the

research changes and how much more there is to know about how to help

those who suffer from the disease. If his wife had the "sham" surgery,

he wants her to get the gene therapy should the trial show promising

results.

Beeri knows it might not

work, but still thinks it was worth doing.

"It will help for the

future, even if it doesn't help us right now."

|

Dr. Jacobo

Mintzer

Dr. Jacobo

Mintzer Gene therapy involves nerve growth

factor being injected into a critical area of the brain called the

Nucleus Basalis of Meynert.

Gene therapy involves nerve growth

factor being injected into a critical area of the brain called the

Nucleus Basalis of Meynert.

Avri

and Dvora Beeri

Avri

and Dvora Beeri