|

By

Dawn Brazell

Public Relations

Sometimes Michael Sweat,

Ph.D., has to eat goat. It's not a favorite part of the MUSC

researcher's job in Africa, but he understands why it's necessary.

"It's a big cultural thing

for them to have these big cookouts with a big goat they've

slaughtered, and you're the honored guest so you have to eat these big

chunks of goat they're giving you."

Sweat grimaces, but then

grins. His willingness to respect the local customs is one reason he

and a team of researchers have had success in an ambitious, eight-year

HIV study that was recently published in Online First "The Lancet

Infectious Diseases." Interim findings from the National Institute in

Mental Health's (NIMH) Project Accept combined data from 10 communities

in Tanzania, eight in Zimbabwe and 14 in Thailand.

Dr. Michael

Sweat holds up a Tanzania map where he oversaw a research team. Dr. Michael

Sweat holds up a Tanzania map where he oversaw a research team.

Thrilled the study shows

the value of community-based voluntary counseling and testing (CBVCT),

Sweat sees this as another step in changing social policy to put a dent

in the tide of the AIDS epidemic that just keeps going. With an

estimated 2.8 million new HIV infections in sub-Saharan Africa in the

past year alone, 24.7 million Africans are now living with the virus.

Dr. Michael Sweat gets water using

a hand pump. This is the type of setting researchers sought out to

provide intervention for local villagers. Dr. Michael Sweat gets water using

a hand pump. This is the type of setting researchers sought out to

provide intervention for local villagers.

"It's a big problem.

There's a huge mortality. There are a lot of orphans from AIDS. There

are a lot of widows and people affected. There are about 9 million

people in Africa who are infected and don't have access to treatment.

There's a big need to do something about it. Our intervention has a lot

of treatment implications."

The goal is to get people

to reduce risk-taking behavior and therefore slow down the transmission

of HIV, but also to get them on treatment because that's a life-saving

intervention, he said. Their study examined the impact of reaching out

to rural communities in creative ways through a four pronged approach

involved in CBVCT. They were:

- Doing mobile HIV

testing to reach isolated communities set up in highly visible sites,

such as the center of villages or water pumps, where villagers were

likely to congregate;

- Enlisting local

community support for greater "buy in" and encouraging fun ways to do

outreach, such as skits and community events;

- Performing

post-testing support to encourage people to disclose status and to

better serve the extensive psycho-social needs of those infected and;

- Using social

marketing techniques, such as feedback loops in the management system,

to constantly monitor the strengths and weakness of the program, and

make changes as you go. This strategy borrows techniques used by

companies such as Coca-Cola.

"You can go to any

developing country in the world and buy a Coke, and there's a reason

for that. These companies know how to do it. They know how to get

people excited about it. They know how to brand these products and make

sure the logistics are in place to get the commodities there. We

borrowed that model. If you can do that in this area, you can also do

it in health."

Interim findings

support what they did worked.

Sweat, who is

director of MUSC's Family Service Research Center in the Institute of Psychiatry, said he had a

Tanzanian local staff of 100 and eight vehicles. One of four U.S.

principal investigators on the multi-country study, Sweat leads the

Tanzania team. He and his group had to create maps of the Tanzanian

areas they served by driving around with GPS and manually recording

where every home was located. They did more than 9,000 interviews and

got blood samples using an exciting new technology that allows them to

see whether an infected person has a new infection or not—important

information in determining transmission patterns.

"This was like a

dream study. These are all people I've worked with for years," said

Sweat, whose impressive resume includes work with the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, Family Health International and 12

years at the Department of International Health at John Hopkins

University.

This community outreach project

involved an educational skit about how women can pass the HIV virus to

their infants. This community outreach project

involved an educational skit about how women can pass the HIV virus to

their infants.

"It was one of

NIMH's biggest studies. It took a long time and a lot of effort, but it

was great. We had the best of the best. We have a statistics center in

Prague who handles a lot of our biostats. We have a data management

center in India that was fantastic. We have a lab at Johns Hopkins that

handles a lot of the laboratory work. It was cool."

There are 52,000

blood samples being shipped from five sites in four countries to

Baltimore for analysis, so in about a year, the group will be

publishing another paper analyzing if transmission rates have dropped.

"We hope it reduces

the number of new infections of HIV. If this were to do that, that

would mean this intervention could be replicated and could slow this

epidemic down. That would be so important. It would lead to a policy

change and people would start doing more door-to-door testing—this

mobile provision in rural areas."

Sweat said the way

they did mobilization created a positive energy about being tested. "It

became normative to get tested—everyone was doing it. A lot of people

felt safe doing it. But I also think putting it where people lived made

the difference. It's a very poor region and a lot of people have to

walk to get to the clinics. It can be a four-hour walk."

One of the goals of

the project was to destigmatize the process of getting tested, and

Sweat knows they were successful in challenging the concept that HIV

testing centers should be hidden away.

"We went in the

totally opposite direction and said we're not going to hide. We're

going right in the middle of the village next to where people get their

water or gather. We want people to visibly have to walk in the door and

be seen by other people. It made it safe for other people, and we got

huge numbers of people coming."

Bringing up Malcolm

Gladwell's book "The Tipping Point," Sweat said the study was not just

about doing "lots of testing" but about affecting cultural change

"It was the idea

that you change norms in the community—that if you get to a critical

mass to a certain tipping point that Gladwell writes about in his

book—where people are talking about it, then you'll have less

transmission from HIV."

It's news that the

United States can use, since research is showing the AIDS epidemic in

the United States is more concentrated among the poor, a factor that

has played out globally. Many of the big breakthroughs the field has

had were discovered by researchers doing work in developing countries.

"It is also notable that

since the rates of HIV infection are so high in many developing

countries, it is much easier to detect if they work there. This allows

us to benefit from this knowledge in the U.S."

Sweat likes how

international research can shed light on health disparities at home.

Having already submitted another grant proposal, Sweat said MUSC's

focus on globalization is impressive and that he has found it to be a

supportive environment. It probably means eating more goat in his

future.

For more

information:

Project Accept is the first

international randomized controlled Phase III trial to determine the

efficacy of a behavioral or social science intervention concerning the

incidence of HIV. The Project Accept website is http://www.cbvct.med.ucla.edu/.

For the full text version

of the study published in Online First in "The Lancet Infectious

Diseases," visit http://www.thelancet.com/journals/laninf/article/PIIS1473-3099(11)70060-3/fulltext.

Spotlight on Research

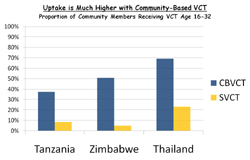

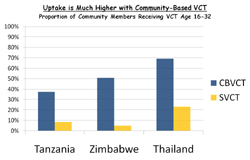

In the study,

communities in each setting were paired according to demographic

characteristics, and one of each pair was then randomized to receive

either standard, clinic-based voluntary counselling and testing SVCT

alone, or SVCT and community-based voluntary counselling and testing

(CBVCT).

The researchers found that the

proportion of people receiving their first HIV test from the study was

higher in CBVCT communities than in SVCT communities in Tanzania (37

percent vs 9 percent), Zimbabwe (51 percent vs 5 percent), and Thailand

(69 percent vs 23 percent). The researchers found that the

proportion of people receiving their first HIV test from the study was

higher in CBVCT communities than in SVCT communities in Tanzania (37

percent vs 9 percent), Zimbabwe (51 percent vs 5 percent), and Thailand

(69 percent vs 23 percent).

Repeat

HIV testing in CBVCT communities increased to reach an average of 28

percent across the three countries.

|

Dr. Michael

Sweat holds up a Tanzania map where he oversaw a research team.

Dr. Michael

Sweat holds up a Tanzania map where he oversaw a research team. Dr. Michael Sweat gets water using

a hand pump. This is the type of setting researchers sought out to

provide intervention for local villagers.

Dr. Michael Sweat gets water using

a hand pump. This is the type of setting researchers sought out to

provide intervention for local villagers.

This community outreach project

involved an educational skit about how women can pass the HIV virus to

their infants.

This community outreach project

involved an educational skit about how women can pass the HIV virus to

their infants. The researchers found that the

proportion of people receiving their first HIV test from the study was

higher in CBVCT communities than in SVCT communities in Tanzania (37

percent vs 9 percent), Zimbabwe (51 percent vs 5 percent), and Thailand

(69 percent vs 23 percent).

The researchers found that the

proportion of people receiving their first HIV test from the study was

higher in CBVCT communities than in SVCT communities in Tanzania (37

percent vs 9 percent), Zimbabwe (51 percent vs 5 percent), and Thailand

(69 percent vs 23 percent).