|

by Dawn Brazell

Public Relations

On the surface,

crocodiles in the renowned Kruger National

Park and the oil spill along America's

Gulf Coast may not seem to have much in

common — unless you're MUSC researcher

Louis J. Guillette Jr., Ph.D.

The reproductive

endocrinologist and a developmental

geneticist is involved in studies in both

regions to figure how chemicals and

contaminants interact with the environment

in ways that impact human health. His

research is confirming just how dramatic

and far reaching these impacts can be.

Dr.

Louis J. Guillette in South Africa.

Watch a video at Dr.

Louis J. Guillette in South Africa.

Watch a video at

http://bit.ly/Dr_Louis_Guillette_Jr.

That's a subject Guillette, director of

the Marine Biomedicine & Environmental

Sciences Center, explores in a reflective

piece published in Science magazine titled

"Life in a Contaminated World." (http://www.sciencemag.org/content/337/6102/1614.summary)

The article commemorates the 50th

anniversary of Rachel Carson's book

,"Silent Spring," that challenged thinking

that up until the early 1960s saw

pesticide use as simply a benefit to

agriculture and public health with few

detrimental consequences. Guillette

observes in the article that the book was

the start of a debate that continues to

this day on the relative benefits and

risks of not just pesticides but of all

synthetic chemicals.

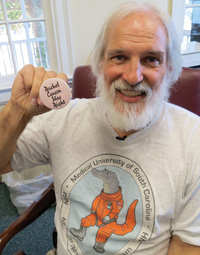

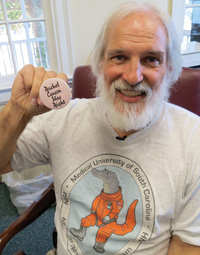

Guillette shows

off his 'Rachel Carson was right'

button. Guillette shows

off his 'Rachel Carson was right'

button.

His goal: To get

researchers, doctors and the public asking

the right questions.

"It's time. A

revolution is taking place. The new

realization is that your health is a

combination of what you inherited from mom

and dad, but also the environment you saw

from the day you were conceived. It's no

longer diseasecentric in that you have a

mutation and it's a predisposition for

disease," he said, adding that a person's

diet and lifestyle, level of stress and

exposure to chemicals that act as

endocrine disruptors all could be factors

leading to such conditions as diabetes,

obesity, cancer or infertility.

"It's not just your

genes. The idea is there is far more you

in your health than just what is inherited

from mom and dad. Your daily actions

actually have a much greater impact, not

only on your health but the health of your

children and even your grandchildren. This

potentially has a multi-generational

effect."

The reason Guillette is

so passionate and gives dozens of public

health talks every year is that he sees

the impact of how chemicals and

environmental contaminants can mimic

hormones and act as endocrine disrupters.

Endocrine disruptors

can create issues from infertility to

obesity by mimicking the actions of

naturally-occurring hormones in the body

or preventing the hormones produced. An

example is how the liver handles

excretion.

Researchers are

studying compounds that act as obesogens

that encourage the body to store fat and

re-program cells to become fat cells or

the liver to become insulin resistant.

In his wildlife biology

research for the past 20 years, Guillette

has found infertility and reproductive

issues in alligator populations from

Florida to South Carolina. Mammals use

hormones that are identical to what

reptiles use, which is why alligators and

crocodiles serve as typical research

subjects for Guillette as sentinel species

to study environmental impacts on human

health.

Into the Wild

Guillette was asked to go to South Africa

to Kruger National Park to examine why

almost half of the crocodile population

there has died off in the past two and a

half years. He went in September for a

couple of weeks to catch and test

crocodiles, getting chased by

hippopotamuses and driving through

maternity herds of elephants.

Dr. Guillette,

who traveled with armed guides while

doing research in Kruger National Park,

took time to photograph the wonders of

the region. Dr. Guillette,

who traveled with armed guides while

doing research in Kruger National Park,

took time to photograph the wonders of

the region.

"You would come around

a bend and there would be a lion. It's

like being in Africa 100 years ago," he

said.

It was, except that this area is a

low-lying drainage basin and the

crocodiles are in trouble, as well as

catfish. "I do know crocodilians, and

there are some things that don't measure

up. Something is going on. The park is an

environmental wonderland, a place that

people come from all over the world to

visit. It resembles New Orleans as far as

environmental problems in that it's a

low-lying area susceptible to contaminants

that are transported in rivers from all

over the country."

Guillette said the

initial four year study in South Africa

will be an interesting collaboration, as

will be the three-year BP trust

fund-sponsored Gulf of Mexico research

grant. Guillette and colleagues Demetri D.

Spyropoulos, Ph.D., Satomi Kohno, Ph.D.,

and John E. Baatz, Ph.D., landed a $1.2

million grant from the Gulf of Mexico

Research Initiative to study the effects

of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill on the

gulf.

The study, "Using

Embryonic Stem Cell Fate to Determine

Potential Adverse Effects of

Petroleum/Dispersant Exposure," involves

the latest in innovative testing methods

that takes advantage of where the

researchers have set up shop.

Although the Hollings

Marine Labarotory is a National Oceanic

and Atmospheric Administration

(NOAA)-administered facility, it is a

fully cooperative enterprise with

activities governed by the five partner

organizations that include MUSC and the

National Institute of Standards and

Technology (NIST).

"It's not just great

science we're proposing, but it is also

the setting that provides us a step up

compared to lots of places. We have this

unique community that we have built and

continue to build. It validates the marine

biomedicine model we have of having a

medical school partnering with NOAA and

NIST and world-class analytical chemists

and biologists."

Into the Lab

Guillette and colleagues have worked

extensively for years trying to find out

how environmental contaminants and native

hormones influence gene expression via

steroid receptors – acting as mimics of

estrogen, progesterone and testosterone.

The question was how to screen chemicals,

in this case the petroleum and dispersant

chemicals, in a way to avoid testing a

wide array of wild animals.

Fortunately, together

with Spyropoulos, Kohno and Baatz, they

had insights based on their research

programs that could contribute a new

approach to testing environmental

chemicals.

They've developed a

technique that can take the estrogen or

progesterone receptors from the more than

40 marine animals that have been cloned

and put it into a cell with a reporter

construct so that when researchers add a

chemical, it binds to the receptor, said

Guillette.

"That is translated to

the reporter, binds to the reporter and

turns on a gene and the cell glows, and it

does it in a dose-dependent fashion. Now

you can say this chemical can be an

estrogen or a progesterone or whatever,

and determine the dose. It lets us know we

now have an active compound to study."

Spyropoulos and Baatz

also have been able to harvest lung cells

from pygmy sperm whales and make inducible

pluripotent stem cells where they took

lung cells and "drove them backwards

developmentally." Guillette said they'll

be able to take aged oil or whatever

substance they're studying and test it on

cells to see if it changes the

developmental process, so instead of

stimulating muscle cell growth, the

treated cell becomes a fat cell, for

example.

"There's a whole world

out there we realize of compounds called

obesogens. These are chemicals that in the

developing embryo instead of stimulating

the production of muscle or fiberblast

cells, it actually stimulates more fat

cells. The chemicals and contaminants in

the diet during embryonic development may

be programming that body to store more

fat."

The Gulf of Mexico

research initiative received 629

applications and MUSC was one of 19

chosen. The initiative is helping to build

a portfolio of top scientists who are

working together.

"The hope is that

although the projects are solicited as

individual investigator-driven projects,

by sharing this information, we are

building a community that is interested in

finding out what's going on. We can start

to get some idea about whether we should

be concerned and where we need to do more

work."

There are several

chemicals that are common, such as BPA

found in plastics and tri-butal-tin found

near harbors around the world, that have

been suggested to have obesogenic

activity. Guillette said their BP study

can't answer everything, but they know how

to be selective in their focus to find

those chemicals that do disrupt endocrine

cycles.

"We know that obesogens

are a critical component and that things

like estrogens and androgens are critical

for long-term and short-term fertility. We

know that glucocorticoids or stress

hormones are associated with inflammation

and immune function. We can take human

glucocorticoid receptors, whale and

alligator and fish glucocorticoid, and

line them up in different cells and test

the chemicals all at the same time. Then

we can see if the chemical potentially

interacts with the receptor that is

associated with stress and immune

function, and we can also test if it goes

across species."

The Carson

Connection

Their work builds on what Rachel Carson

believed decades ago, even without the

scientific testing methods that

researchers have today. If Carson were

alive today, he'd like to tell her thank

you and that she was right. He's proud to

be following in her footsteps.

"If I told you that in

a week you're going to get 2,000 chemicals

in your body that your grandparents never

had in their body, and we have no idea

what the health consequences are, and not

just in you – it's in your kids too. Would

you think that was good?"

The revolution happening is that

scientists from critical disciplines are

joining forces to change the way this game

is played, he said.

"We're coming together

to say as biologists, as health

professionals, as chemists, we need to

start working together. Chemists need to

start taking toxicology and health

classes, and biologists need to start

working with chemists."

It's an immense

undertaking and one still surrounded in

controversy, but Guillette sees the

science winning out.

"We're supposed to be

bright people. We're supposed to be

leaders in the world in innovation. Let's

start innovating. And you know what?

There's money in that. There's real money

in that because a proprietary chemical is

always going to make you more money than

something that's 50 years old. If that's

your vested interest, that's fine. For me,

I just want healthy kids."

Friday, Jan.

11, 2013

|

Dr.

Louis J. Guillette in South Africa.

Watch a video at

Dr.

Louis J. Guillette in South Africa.

Watch a video at

Dr. Guillette,

who traveled with armed guides while

doing research in Kruger National Park,

took time to photograph the wonders of

the region.

Dr. Guillette,

who traveled with armed guides while

doing research in Kruger National Park,

took time to photograph the wonders of

the region.